Develop Your Own Philosophy, Damn It!

And Why it Matters

For the last 13 years, we have been trying to educate with a singular aim: to help people develop and refine their own philosophy.

The consequence of not doing so is to constantly be at the whim of someone else’s will, to consistently be inconsistent, to regularly be a hypocrite, to have no basis upon which to justify, test, and validate your beliefs, decision-making, and intuitions, and to ultimately be civically irresponsible and even dangerous.

It would be impossible to overstate the relevance and importance of learning basic philosophy (and its offspring, science) literacy.

In order to become a more informed and moral being and citizen, to be able to differentiate rhyme from reason, rhetoric from fact, reality from fiction, misinformation from information, sophistry from wisdom, to develop as an independent and autonomous creature with agency, capable of critical and reasoned thought requires learning and, unfortunately, hard work.

Read until you bleed, as I like to say!

Maybe you fashion yourself a super genius capable of intuiting calculus like Newton or observing the behavior of matter and deducing quantum mechanics on your own but color me skeptical of that sort of grandiose claim.

You don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Humans just like you and I, and arguably far smarter, have spent millennia working through the possible nature of our universe, how to live a good life, how to create flourishing societies, and have come up with some pretty nifty stuff. You really should check out all the things we have come to learn and know. It’s pretty impressive.

Don’t be shy! Stand on and leverage those broad shoulders.

As an aside and little anecdote, I once encountered a young gentleman who claimed to not need to read books as he had already figured everything out on his own.

Okay, Napoleon, back into bed. Take your antipsychotics!

Sorry, please don’t mistake that last quip as poking fun at mental illness. Pretty sure this was just an arrogant kid suffering from nothing more serious than Dunning-Kruger.

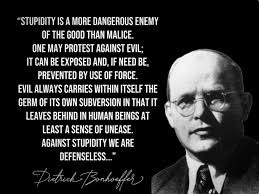

There is no shame in ignorance as we are all ignorant to the majority of knowledge that can be acquired but when one lacks even the curiosity or interest in addressing their ignorance, it manifests as stupidity and stupidity is far less justifiable than ignorance.

But the consequences are the same, regardless of the cause.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer went as far as to assert that stupidity is worse even than malice.

And Heinlein taught us the useful Hanlon’s Razor heuristic to remind us that ignorance may be as responsible for the ills and failures of our world as malice and to distinguish between the two.

When your mind tries to justify your sense of powerlessness, your need to succumb to simple answers, your desire to feel special and “in the know,” and to regurgitate some old tired and long debunked conspiracy theory or appeal to an all-knowing imaginary father figure and some divine inexplicable purpose, try to remember that human incompetence and stupidity can go a long way at explaining many phenomena.

Why does developing a consistent and internally coherent philosophy matter beyond just an individual’s moral and intellectual growth?

The most self-evident of answers is because we live in a global society with increasingly serious global issues to solve together; that our very nature is one of a social animal and that our beliefs, desires, attitudes, and behaviors affect others, arguably all 8 billion of us at scale.

Having said all that, you are always free, if you wish, to forego all of the benefits of thousands of years of scientific and philosophical knowledge and go Robinson Crusoe on your fine self.

Plato was so concerned by the problem of ignorance and our “appetites” that he warned us explicitly about our inabilty to self-govern and about the ills of democracy itself.

He argued that democracy ultimately leads to chaos and tyranny. He warned us of the power of demagogues, mob rule, and our susceptibility to unreason.

“The people have always some champion whom they set over them and nurse into greatness… This and no other is the root from which a tyrant springs.”

— Republic, Book VIII

While Plato believed that we required a paternalistic answer to self-governance, and as admittedly fond as I am of the romantic notion of a highly educated, virtuous and ethical committee of philosopher kings (and queens) dedicated to managing, guiding, and informing us on how to live a good life together, we have yet to solve for the problems of human greed, corruption, and incompetence.

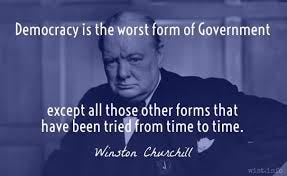

So, until something better comes along, I reluctantly must concur with the reasoning of Churchill,

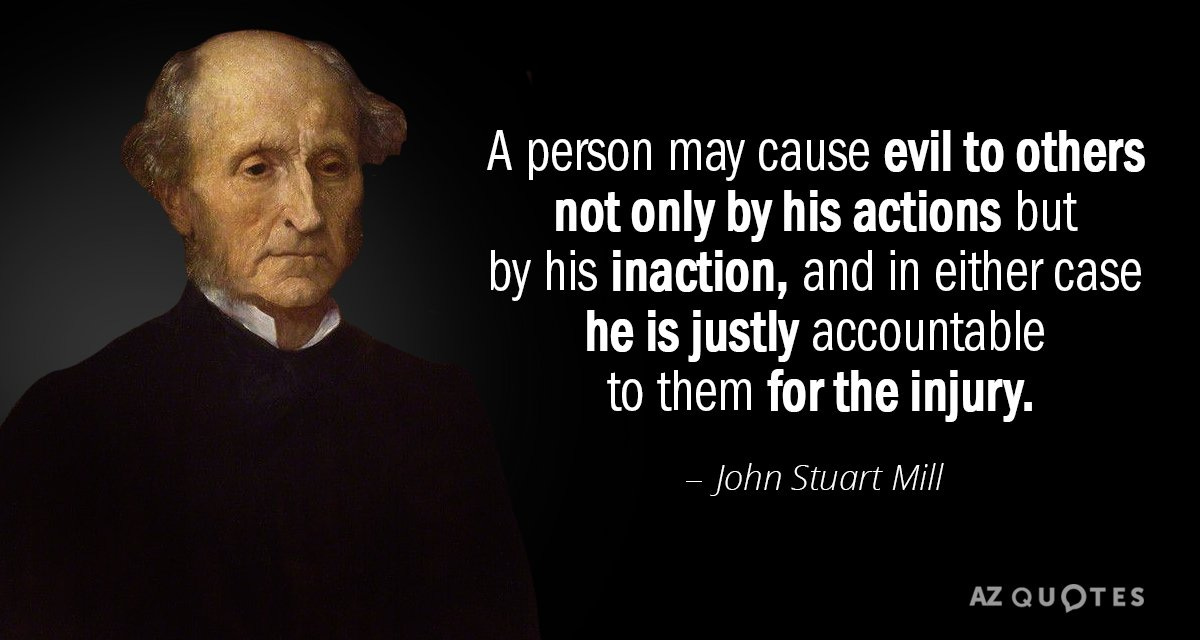

John Stuart Mill, among many other political and moral philosophers, famously made a far more robust argument in defense of democracy but equally understood the problem of ignorance and that the value of democracy was determined by the quality and sophistication of its constituents,

“The worth of a state in the long run is the worth of the individuals composing it.”

— On Liberty (1859)

Mill advocated that the antidote for a strong democracy was public education, free speech, and open debate.

He was a strong libertarian and elaborated at length on his harm principle that to the extent that we do not harm another, we should be free to “speak, act, and live as we see fit, without molestations from individuals, law or government.”

Notably, he also argued that we were responsible for any harm we caused others from both our actions and inaction, thus suggesting we all have a moral obligation to also help others.

Take that Ayn Rand!

What many modern sources who promote democracy don’t tend to discuss, however, is how similar even the beliefs of the American founding fathers were to Plato’s philosopher kings concept. They, to one degree or another, understood governance as being decided only by a small committee of the most educated and virtuous. In their case, that translated to white land-owning men.

The idea of universal suffrage emerges slowly over time and begins to take hold only in the 20th century. But it is because of documents and arguments made far earlier that it became increasingly more untenable to defend institutions like chattel slavery and to deny equal rights to women and minority groups.

The evolution of concepts like democracy, individual rights, agency, and autonomy, freedom, self-governance, and ultimately universal suffrage and human rights has changed dramatically over the millennia.

And we have reason and developments in political and moral philosophy to thank for that.

If you’d like to see a beautiful defense of the power of reason itself, I highly recommend that you watch an animated Socratic dialogue on the topic between Steven Pinker and Rebecca Goldstein,

These modern ideas emerge from the Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights, The Renaissance, The Scientific Revolution, Locke’s treatise on natural rights, the Protestant Reformation, The European Enlightenment, and the French and American Revolutions.

Despite all the robust defenses of democracy and individual freedom over the ages, what happens if and when they fail?

Hannah Arendt, one of the most influential political philosophers of the 20th century, had a lot to say about that sort of thing. She was well situated to do so and is often cited as one of the most preeminent authorities on totalitarianism, the nature of evil, and the human condition.

She argued, similarly to Plato, that it is the central problem of thoughtlessness and ignorance that creates the preconditions necessary for authoritarianism and evil to propagate. She demonstrates compellingly how, in the contexts of both Nazism and Stalinism, they were able to seize power by exploiting apathy and ignorance.

She may be most known for developing the concept of the “banality of evil;” how the lack of critical thinking of ordinary people can lead to committing atrocities.

This salient quote is so central to the hypothesis that reason matters, that developing independent thought and critical thinking matters; that being able to distinguish fact from fiction is not only merely a beneficial individual human skill but absolutely necessary to a healthy, free, and flourishing society.

So, I wish upon and implore all of you to learn and develop your critical thinking skills, to develop an internally consistent moral and intellectual philosophy.

You owe it to yourself. And we owe it to each other and our children.

I have long made the argument that to become a truly good thinker and a more moral being, you need to satisfy two prerequisites.

You need a valid framework, foundation, a set of tools and methods: an intellectual and reasoned basis upon which to evaluate all truth claims and you need a vocabulary or database of knowledge and facts. This latter bit requires basic science literacy.

You need to learn the basics of ontology, epistemology, and axiology.

You need to learn, develop and constantly refine a theory of knowledge (TOK) in order to understand the difference between belief, knowledge, and dare I say, truth. And you need to learn what constitutes and justifies appealing to those words in a sort of hierarchy of epistemic confidence, whereby you treat those concepts and their distinctions with the care they deserve.

You need to learn how we come to assert what is real and what is not and upon what basis we can morally claim to know what is right and wrong.

And don’t ignore the option to reserve judgment sometimes, especially when the evidence is just not there or compelling.

I submit this well known quote which is usually attributed to another one of our good friends, Aristotle. I highly recommend you give him a read if you find time. Smart fellow. Has a lot to say about ethics and logic.

So, if you managed to endure my long stream of consciousness here and think that this is all mindless drivel, word salad, hogwash, and mere mental masturbation and that none of this is relevant to you or anyone else, you might want to note another warning from Plato,

Hi! Great post. I'd be grateful if you'd read my post, the first of several dealing with my new passion for philosophy.

https://substack.com/inbox/post/167139062?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=6q1bt&fbclid=IwY2xjawLT4NlleHRuA2FlbQIxMQABHv4ni-CurdMQbxZw3ozsN_k8_wyshQr1EhDuKYIOmvoOqQFme7Hg6h9UoOvT_aem_SL2AmT2c0ASoWquoHWkABg&triedRedirect=true