There Are No Capitalist, Socialist, or Communist Countries!

Stop saying there are!

If you care about becoming a better and more honest critical thinker, a better conversationalist, or a strong debater, you have to actually learn and practice certain skills.

You need to develop a basic understanding of linguistics, semantics, argumentation, formal reasoning, and logic. A spot of appropriate humor and charm won’t ever hurt either. :)

As a longtime critical thinking educator, I’ve always tried to promote the ideas of clarity and precision of thought. I’ve tried to teach the basic logical fallacies, cognitive biases, and formal reasoning so that people can improve their argumentation skills and avoid not only bad faith but the common traps many fall into which render discussions either fruitless, frustrating, or both.

If we wish to communicate effectively, it’s important that we can find agreement on the meaning of words, for example, and to act in good faith to try to better understand each other.

”Steelman, don’t strawman,” I always say! Actually, I’ve never said that but I should.

or

”Words mean things, damn it! That word doesn’t mean that.” Now, that I say all the time.

No debate or serious discussion should even begin before all parties can agree on the actual conversation to be had.

You might notice if you follow formal debates that they spend a lot of time before even beginning on the exact formulation of the proposition.

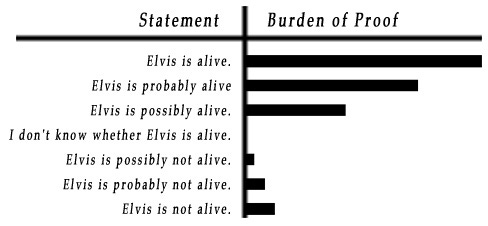

The choice of a positive or negative proposition can change entirely the burden of proof required by both parties.

If you understand the below chart, you get it.

The simplest of examples might be a debate where the proposition is “there is a god” versus the proposition “no god exists.”

These two propositions would entail completely different debate approaches and lines of reasoning. In the former, the pro side would have to make a reasoned and/or empirical case that something exists while the latter proposition would require the pro team to make a reasoned and/or empirical case that something does not exist.

If I were to participate in one of these two debates, I would much prefer to be on the con team regarding the first proposition than to be on the pro team of the latter. It would make for a far easier debate.

The reasoning behind that position reduces to the more complex nature of trying to demonstrate or argue that no such thing can possibly exist in our universe or even possibly beyond our universe, if the word beyond has any meaning in that context.

If I were, however, to do so, I imagine my efforts would be concentrated on unlikelihood or the absence of any positive evidence, or maybe I would just focus on the word itself being ambiguous and possibly incoherent and unfalsifiable.

It is because we cannot claim to have explored and investigated the entire universe or to know that there is nothing “beyond” that it would be a daunting task.

However, if we are constraining a debate to phenomena on just this planet, it would be far easier to argue that something does not exist, depending on the topic, of course.

While I might not assert confidently that a primitive hominid-like creature, maybe something referred to as a Yeti or Bigfoot, does not or cannot exist on Earth, I would feel far more confident asserting that there are no flying elephants.

He would probably be a cute little bugger though!

In this context then, let’s have a chat about political philosophy, political science, political economy, and economics.

As both a political scientist and economist, I have always promoted the idea of trying to parse economist systems from governance systems. I think it allows for easier analysis, better clarity, and consistency.

I concede that most of the time certain economic and political systems are paired and for some pretty obvious and practical reasons. It is more likely, for example, to pair a democratic governance model with a capitalist economic system, whereas it’s less likely to find a communist governance system with a capitalist economic system. I’d have to do some mental gymnastics to imagine the latter but I’m sure I could come up with something.

But here is the rub and the crux of this essay.

Are there really any capitalist, socialist, or communist countries at all?

I mean, people certainly all seem to think that they exist. Most would probably discount the question as incoherent or inane.

Lots of people claim that the United States is a capitalist country. But is it?

Lots of people claim that the Scandinavian countries are socialist countries. But are they?

Lots of people claim North Korea and maybe even Cuba are communist countries? But are they?

It turns out the answers are a tad bit more complex, and arguably “no.”

Let’s start out with that whole distinguishing between governance and economics thing. Because, as usual, a lot of things don’t tend to be as binary as we would like them to be. Simple answers are convenient and make us feel better but the universe very rarely serves us up much simplicity.

A common method of analyzing both governance and economic models is to understand them as being on a spectrum, rather than as binary sorts of things.

In that context, we might rather ask questions like which nation-states are more “free” or which nation-states allow citizens to vote on their laws or select their leaders.

Freedom is a nebulous sort of word but for the sake of brevity and without going down a rather deep philosophical rabbit hole, let’s just presume some standard qualifications where we understand individual freedom to be better served by democracy and less well served by totalitarianism.

Now we have a spectrum of possible governance systems. But again, simplicity is not readily available, so we need to parse even further.

Of the approximate 200 nation-states in the world, estimates are that anywhere between 50% to as high as 96% of nation-states can be considered democracies.

The Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index classifies countries into "full democracies," "flawed democracies," "hybrid regimes," and "authoritarian regimes.”

In their latest report, they found that only 24 countries are considered full democracies, while 46 are classified as flawed democracies.

The Pew Research Center reported that 57% of countries with populations over 500,000 were democracies in 2017, but also noted that many countries exhibit both democratic and autocratic characteristics.

Other organizations, like Our World in Data, suggest that about half of all countries are democracies.

As you can see, even the rather simple question “how many nation-states are democracies” does not have a simple answer.

The more appropriate questions might be therefore, “which countries are more democratic or less democratic?” or “which countries are more autocratic or less autocratic?”

Consistently, the answer most given by most legitimate research institutions is that the Scandinavian countries tend to score the highest on most indices for most democratic nation-states, while China, Russia, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, and several nations in the Middle East and Africa, the least democratic.

Let’s move on now to economic systems and limit our selection to the most common cited modern economic systems: capitalism, socialism, and communism.

Let’s begin with capitalism

We might ask a question like “which nation-states are characterized by high levels of economic freedom, private property rights, and free market principles.”

To that question, a good answer might be Singapore, Switzerland, and Hong Kong or other countries like Australia, Ireland, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Estonia.

Those answers might be empirically strong ones if the question is which nations are most capitalistic.

Now, socialism

How about if we ask the question, “which nation-states are characterized by resources and the means of production being owned or regulated by the community or state.”

The primary distinction here is between a market-based, profit-oriented economic system where private property is protected and prices float as a function of supply and demand and a command-based, centrally planned economy where property is allocated as a function of need and not based on profit.

Note that this distinction does not inform us as to whether either system is authoritarian, only which economic model is employed.

Looking for modern nation-states that would qualify as socialist does not provide us with a satisfactory answer or example. We might point to Maoist China or the Soviet Union, neither of which currently exist.

And neither of them allowed for any worker or public democratic control over the economy.

Were those socialist nation-states? Not really.

Autocratic? Certainly. Both are largely considered to have been totalitarian regimes at their origin and slightly liberalized into authoritarian regimes in the latter years.

Let’s do communism now

Communism, as envisioned by Marx, was the inevitable end result of the transformation from an initial capitalist system which ultimately fails due to its profit motive and inequality, an ensuing revolution with the working class overthrowing the aristocratic class, to a socialist command-based economic system which distributes wealth equitably, and ultimately to a state-less society without any class structure or hierarchy, no wage labor or money, and the eradication of scarcity.

His notion was of a utopian egalitarian society.

While countries like USSR, China, North Korea, and Cuba tried, they never managed to get to a stateless, classless, moneyless society. Rather the state became even more powerful and turned authoritarian or totalitarian.

A communist nation-state has never existed.

A socialist nation-state has never existed.

A capitalist nation-state has never existed.

Every nation-state system to date, whether we are referring to governance or economics has been a hybrid of some sort or mixed, if you prefer that word.

A better way to discuss and understand governance and economic systems, or political economy, is to discuss nation-states in the context of:

Degrees and types of freedoms

Property rights and protections

Levels and types of state services

Degrees and types of market and monetary intervention

So, stop talking about capitalist, socialist, and communist nation-states unless you wish to talk political theory because they don’t exist in practice.

Words mean things, damn it! Those words don’t mean what you think they do.

If you’re discussing the distinction between the United States and the Scandinavian or European countries, for example, it is technically incorrect to say that the former is a capitalist nation-state and the latter are socialist nation-states.

They are all liberal democracies with a mostly market-based economy and differing levels and types of social services and degrees of market intervention.

Excellent analysis! It matters that we don't waste our time arguing ideaologically over a false dichotomy and focus on fine tuning our position on the spectrum.